Image source, Emma Ash

Image source, Emma AshImage caption,

It’s not unusual for Emma Ash to jump onto YouTube to watch a video of how to repair yet another electrical item that has suddenly stopped working.

The 46-year-old also routinely picks up old items from car boot sales, or even skips, to fix and refurbish them.

“I’m a granddaughter of a generation who really believe in making do and mending,” says Ms Ash, who lives in West Berkshire.

“It’s always been part of my life. I’m all about saving things.”

The boss of YoungPlanet, an app that allows parents to donate no longer needed kids’ toys and clothing to other parents, she managed to fix a fridge during lockdown.

She has also resolved a leaking toilet, and mended a broken vacuum cleaner.

“It’s always worth a shot,” says Ms Ash. “It’s hugely satisfying because invariably it doesn’t cost as much as getting someone else out.”

Image caption,

With many of us having to cut back on our spending due to the rising cost of living, there has been an increase in the number of people repairing goods, instead of replacing them with a new purchase.

Add in environmental concerns and a report earlier this year found that a quarter of Londoners are now repairing more than they were in 2020.

Nationwide more than half of people said they had repaired something in the past year, according to last month’s Sustainable Consumer 2022 report by accountancy group Deloitte.

Given that around the world as much as 50 million tonnes of electronic item waste alone is produced per year, of which only 20% is formally recycled, and it is hard not to agree that this increased repair work is a good thing.

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

However, certain home electrical products are easier to fix than others.

For example, some 42% of people in the UK have successfully fixed a vacuum cleaner, or would be “comfortable” to give it a go, a report found last year. Yet for televisions the number falls to 14%, and to just 10% for microwave ovens.

Whatever electrical item you think about fixing, it is obviously important to work as safely as possible, and ensure that the item is unplugged before you start.

What should start to make repairs easier are the new “right to repair regulations” that came into force for England, Scotland and Wales last summer.

Mirroring similar European Union legislation that applies to Northern Ireland, they legally require manufacturers of electrical goods to start making spare parts available to buy. There are however, exemptions, for smartphones and laptops.

To help give people more confidence to try to repair things, a growing number of individuals and organisations are taking matters into their own hands, and organising ‘repair cafes’ – both in the UK and overseas.

Image source, Mark A Phillips

Image source, Mark A PhillipsImage caption,

More often held in a communal space, such as community hall, library or church building, the idea is that people can take along broken electronic items, and volunteers will help fix them, or offer advice.

“It isn’t just about getting something repaired, it’s about learning new skills and feeling empowered to maintain your own products,” says Ugo Vallauri. He is co-director of London-based Restart Project.

There are now an estimated 2,400 such repair cafes worldwide, and more than 250 in the UK.

Earlier this year, Restart Project also launched two permanent sites or “Fixing Factories” in London. In Camden and Brent volunteers repair people’s broken electronics on a pay-what-you-like basis.

Image source, Mark A Phillips

Image source, Mark A PhillipsImage caption,

“We’d like to turn it into a national network of similar places, and want repair to become the norm,” says Mr Vallauri.

“Everyone should have access to repair, and it should be the first option when something breaks rather than giving up and clicking on next-day delivery for something new.”

When it comes to clothing items, there are also new, convenient ways to get items fixed rather than have to buy replacements.

Website-based Make Nu allows users to send off clothing to be repaired and then mailed back. And Sojo is a clothing repair app which works as a marketplace, allowing people to find somewhere to repair and mend the clothes.

Josephine Philips founded London-based Sojo in 2021, fresh out of university. “I was thinking if circular, slow fashion is going to be accessible to a younger generation it needs to be modernised and digitised, and so set about creating a solution.”

Image source, Issey Gladston

Image source, Issey GladstonImage caption,

But with a great many people still scrambling to buy the latest smart phone, ultra-high definition television, or latest clothing trend, is the tide actually turning?

“There is definitely a subculture of people wanting to get things repaired, but it’s very much a subculture,” says Tim Cooper, professor of sustainable design and consumption at Nottingham Trent University.

“Although there are thousands of repair cafes globally, and they have done a great job, they tend to be quite small compared to the millions of products people are buying. We need to move away from a throwaway culture.”

Mr Vallauri adds that what would help boost the number of people repairing their electrical goods in the UK is a tax cut to make it more affordable. “We have been campaigning for the removal of VAT…which exists on repairs of yachts but not on computers or white goods.”

He also points to an initiative in Austria where the government is giving out repair vouchers helping to reduce the cost of repair by 50% up to the value of €200 ($204; £168). There is a similar scheme in the German state of Thuringia.

Meanwhile, last year France launched a mandatory repair score index for some electrical products. For example, when you buy a smartphone or lawnmower you will see a score of 1-10 of how repairable it is.

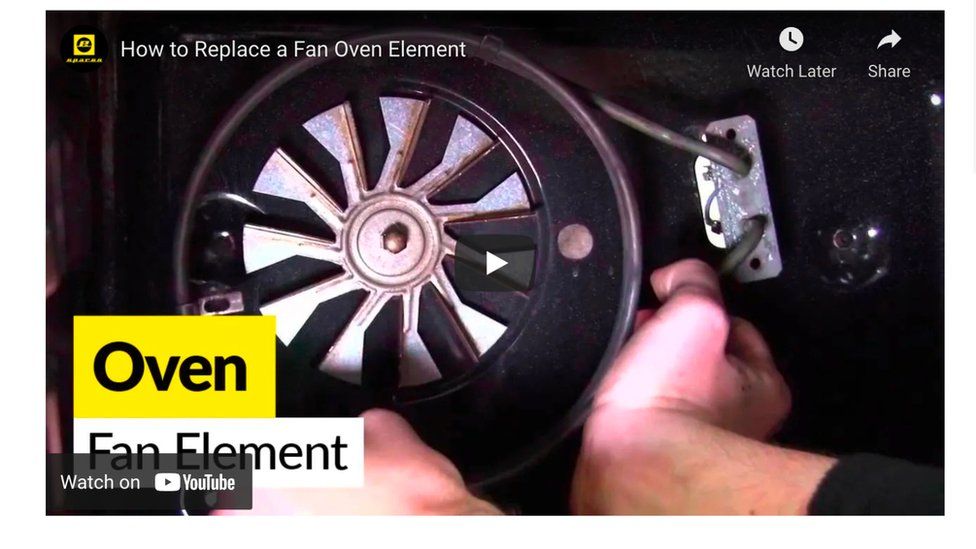

Still, increasing number of people in the UK do indeed seem to be fixing things at home. Espares, a website offering spare parts for everything from fridges to vacuum cleaners, says its UK sales are now a third higher than they were back in 2019.

It posts repair guides on its website and YouTube, and last year it launched a video chat tool enabling people to show their problem to its customer service team.

Image source, Espares

Image source, EsparesImage caption,

“We see a lift whenever people are having to pull the purse strings,” says head of brand Adam Casey. “It’s a no-brainer that instead of, say, paying hundreds of pounds for a new dishwasher they might change the spray arm themselves for £20.”

Back in West Berkshire, Ms Ash advises others to “give it a go yourself”.

“You can always find a video on YouTube of someone fixing whatever fault there is with your item,” she says. “Fixing something gives you a lot of satisfaction and is really empowering.”